Week 5: Regression

RSM338: Machine Learning in Finance

1 Introduction

You already know OLS from your statistics and econometrics courses. This chapter builds on that foundation by asking: what happens when OLS’s assumptions don’t hold, and what can we do about it?

The machine learning perspective on regression differs from the traditional statistics perspective in an important way. In statistics courses, the focus is typically on inference—is the relationship between \(X\) and \(Y\) statistically significant? What’s the confidence interval for \(\beta\)? In machine learning, the focus shifts to prediction—how well can we predict outcomes we haven’t yet observed? This shift in emphasis leads to different tools and different concerns. We care less about whether \(\beta_j\) is “significant” or what its “true” value is, and more about prediction accuracy on data we haven’t seen.

This chapter covers several interconnected topics. We start with OLS as an optimization problem, then examine when and why it fails. We’ll see how to generalize the OLS framework by relaxing assumptions about functional form, loss functions, and coefficient constraints. The central concern throughout is the distinction between in-sample and out-of-sample performance, formalized through the bias-variance trade-off. We then develop regularization methods (Ridge, Lasso, Elastic Net) that combat overfitting, and discuss how to select among models using cross-validation. Finally, we turn to finance-specific applications and pitfalls.

2 OLS as an Optimization Problem

From your statistics courses, you’ve seen the linear regression model \(\mathbf{y} = \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta} + \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}\). OLS is fundamentally an optimization problem: we choose \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}\) to minimize the residual sum of squares: \[\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}^{\text{OLS}} = \arg\min_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \mathbf{x}_i^\top \boldsymbol{\beta})^2 = \arg\min_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}\|^2\]

The notation \(\|\mathbf{v}\|^2\) is the squared norm of vector \(\mathbf{v}\)—the sum of its squared elements: \(\|\mathbf{v}\|^2 = v_1^2 + v_2^2 + \cdots + v_n^2 = \sum_{i=1}^{n} v_i^2\). So \(\|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}\|^2\) is just compact notation for \(\sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2\). The argmin formulation makes explicit what OLS is doing: searching over all possible coefficient vectors \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) and selecting the one that minimizes squared errors. This optimization problem has a closed-form solution: \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}^{\text{OLS}} = (\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{y}\).

OLS is the workhorse of statistics and econometrics for good reasons. Each coefficient \(\beta_j\) tells you how much \(Y\) changes when \(X_j\) increases by one unit, holding other variables constant. The method comes with standard errors, allowing us to test whether coefficients are statistically significant and build confidence intervals. And the closed-form solution means no iterative algorithms are needed—just matrix algebra.

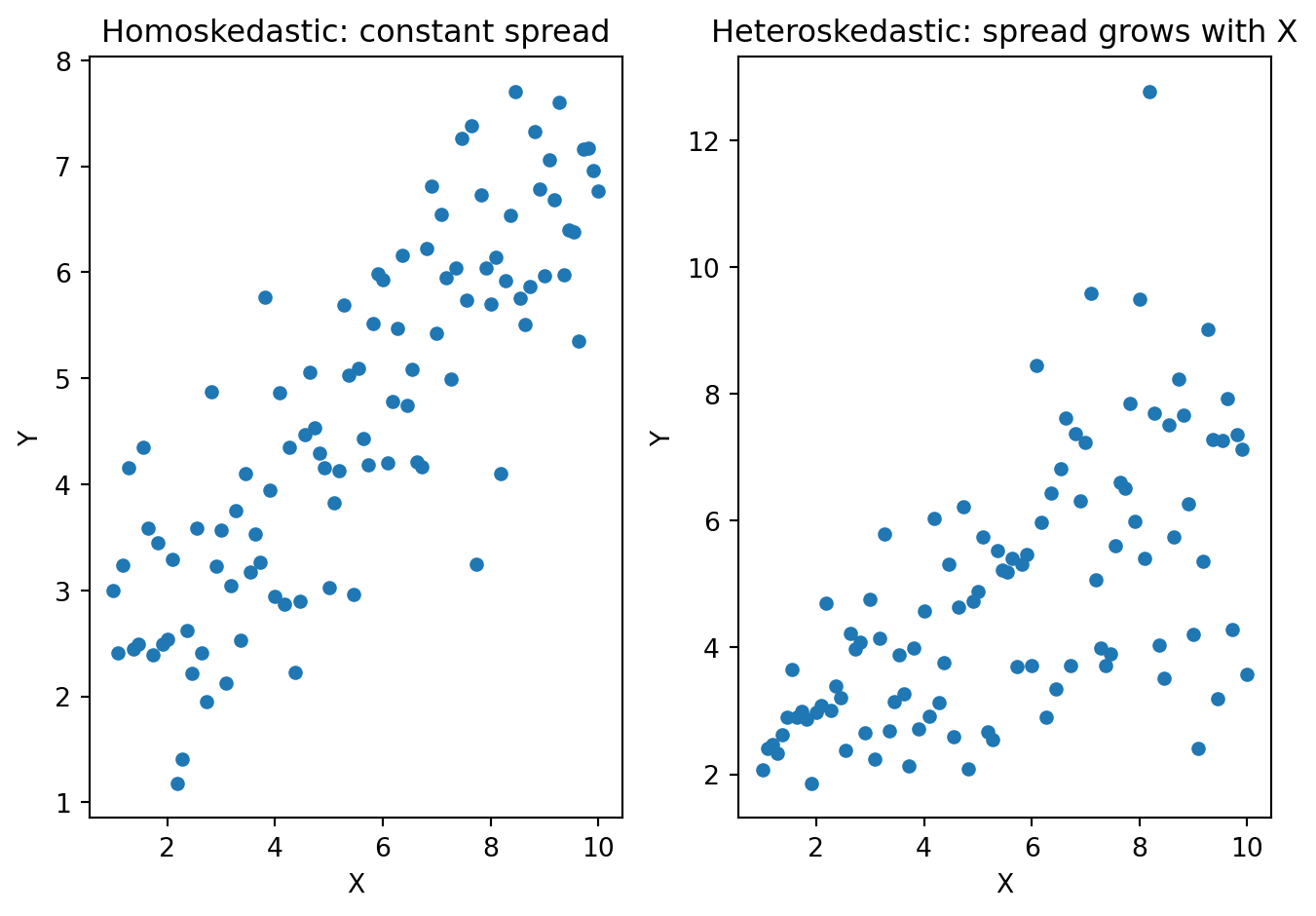

OLS gives reliable estimates and valid hypothesis tests when certain conditions hold. Linearity requires that the true relationship between \(X\) and \(Y\) is approximately linear. Homoskedasticity requires that the spread of errors is constant across all values of \(X\)—“homo” means same, “skedastic” means scatter. The plots below illustrate the difference:

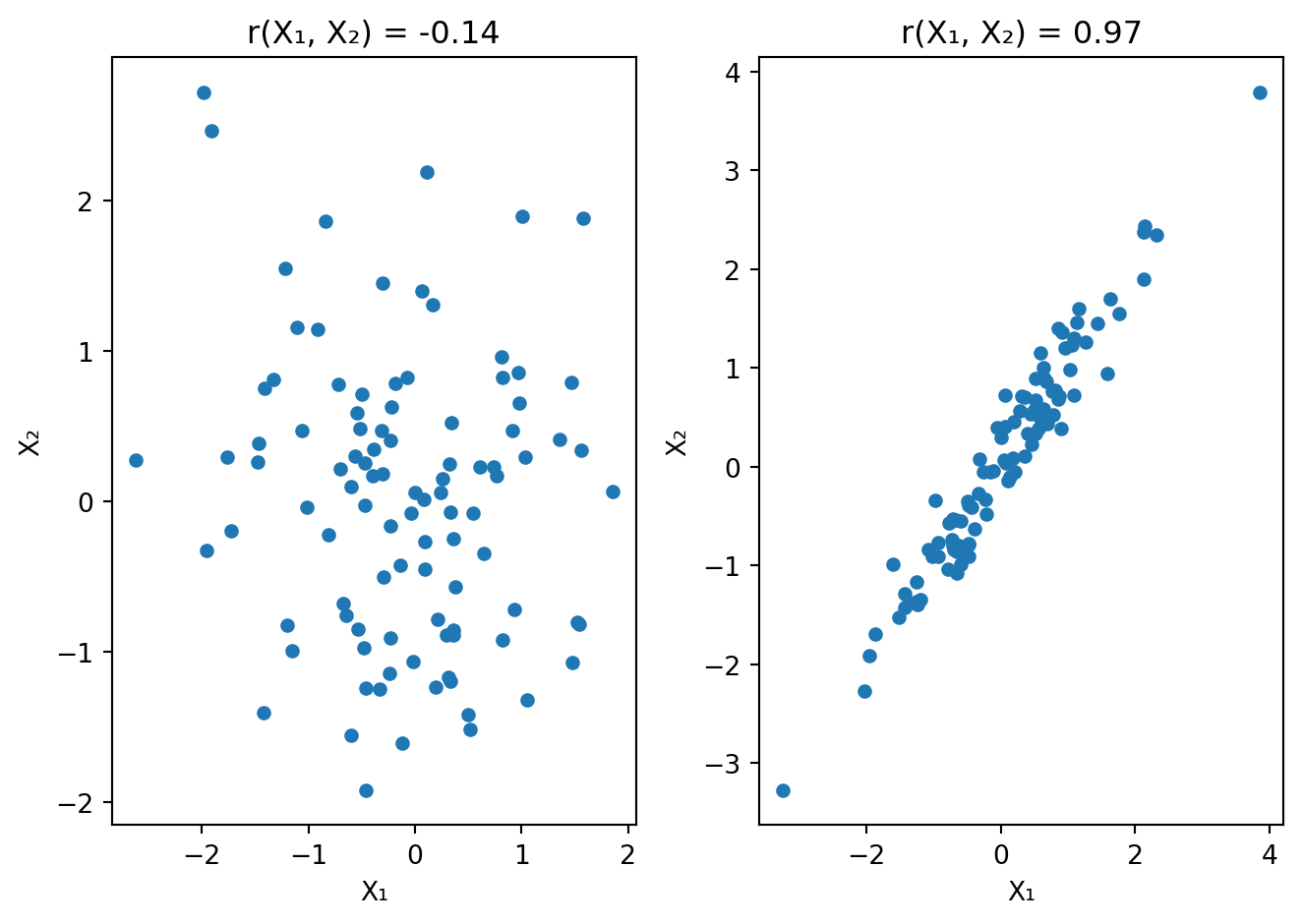

No multicollinearity requires that predictors should not be too highly correlated with each other. When predictors are highly correlated, \(\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X}\) becomes nearly singular—hard to invert. Recall that \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}} = (\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{y}\), so small changes in the data cause large swings in \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}\).

Consider predicting next month’s stock returns from firm characteristics. The econometrics lens asks: Does book-to-market ratio significantly predict returns? What is the estimated effect of a 1-unit change in B/M? Are the results robust to different specifications? The ML lens asks: If I train on 2000–2015 data, how well do I predict 2016–2020 returns? Does adding more predictors help or hurt out-of-sample? What’s the optimal amount of model complexity? Both lenses use regression, but they emphasize different aspects.

3 When OLS Struggles

OLS is a workhorse, but it has limitations—especially for prediction. When \(p\) (number of predictors) is large relative to \(n\) (observations), OLS estimates become unstable; in the extreme case where \(p > n\), OLS doesn’t even have a unique solution. When predictors are highly correlated (multicollinearity), \((\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X})\) is nearly singular, and small changes in the data lead to large swings in coefficient estimates. And OLS uses all predictors, even those that add noise rather than signal—the model fits the training data too well, including its random noise, and generalizes poorly. This is overfitting.

A cautionary tale from finance: suppose you want to predict monthly stock returns using firm characteristics. You have \(n = 500\) firm-months and \(p = 50\) characteristics: size, book-to-market, momentum, volatility, industry dummies, and so on. With OLS, you estimate 51 parameters (50 betas plus intercept), each coefficient has estimation error, many characteristics might be noise not signal, and the fitted model explains the historical data well—but does it predict future returns?

Goyal and Welch (2008) examined this question in a seminal study. They tested whether classic predictors (dividend yield, earnings yield, book-to-market, etc.) could forecast the equity premium. The finding: variables that appeared to predict returns historically often failed completely when used to predict future returns. Many predictors performed worse than simply guessing the historical average. This isn’t a failure of the predictors per se—it’s a failure of OLS to generalize when signal is weak relative to noise. OLS minimizes in-sample error. When the true signal is weak, OLS fits the noise in the training data, and this noise doesn’t appear in the same form in new data. The noise-fitting hurts rather than helps prediction. The coefficients are unbiased in expectation—but they have high variance. When you apply them out-of-sample, the variance dominates. This is the heart of the bias-variance trade-off we’ll formalize later.

4 Generalizing the OLS Framework

OLS makes specific choices that we can relax. There are three ways to generalize: the functional form (linearity), the loss function (how we measure errors), and constraints on coefficients (regularization).

The OLS objective assumes the prediction is a linear combination of the features: \(\hat{y}_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x_{i1} + \beta_2 x_{i2} + \cdots + \beta_p x_{ip}\). But nothing forces us to use a linear function. We could replace \(\mathbf{x}_i^\top \boldsymbol{\beta}\) with any function \(f(\mathbf{x}_i)\): \(\hat{\theta} = \arg\min_{\theta} \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - f_\theta(\mathbf{x}_i))^2\), where \(f_\theta\) could be a polynomial, a tree, a neural network, or any other function parameterized by \(\theta\). We’ll explore non-linear \(f\) in later weeks (trees, neural networks).

OLS minimizes squared error: \(\mathcal{L}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2\). Squared error is convenient (calculus gives a closed-form solution) and optimal under Gaussian errors, but it’s not the only choice. Absolute error (L1 loss), \(\mathcal{L}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} |y_i - \hat{y}_i|\), is less sensitive to outliers than squared error, but has no closed-form solution and requires iterative optimization. Huber loss is squared for small errors and linear for large errors, combining robustness to outliers with smoothness near zero. The loss function \(\mathcal{L}\) defines what “good prediction” means—choose it to match your goals.

Instead of just minimizing the loss, we can add a penalty on coefficient size: \[\text{minimize } \underbrace{\sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \hat{y}_i)^2}_{\text{fit to data}} + \underbrace{\lambda \cdot \text{Penalty}(\boldsymbol{\beta})}_{\text{complexity cost}}\]

The parameter \(\lambda\) controls the trade-off: when \(\lambda = 0\), there’s no penalty and we get OLS; as \(\lambda \to \infty\), the heavy penalty shrinks coefficients to zero. Regularization deliberately introduces bias (coefficients are shrunk toward zero) in exchange for lower variance (more stable estimates). When signal is weak relative to noise, this trade-off can improve prediction.

A norm measures the “size” or “length” of a vector. The \(L_p\) norm is defined as \(\|\mathbf{v}\|_p = \left( \sum_{i=1}^{n} |v_i|^p \right)^{1/p}\). Different values of \(p\) give different ways to measure length. The \(L_2\) norm (Euclidean) is \(\|\mathbf{v}\|_2 = \sqrt{v_1^2 + v_2^2 + \cdots + v_n^2}\)—the familiar distance formula from the Pythagorean theorem and the default notion of “length.” The \(L_1\) norm (Manhattan) is \(\|\mathbf{v}\|_1 = |v_1| + |v_2| + \cdots + |v_n|\)—the sum of absolute values, called “Manhattan” because it’s like walking along a grid of city blocks.

Now we can define our regularization penalties using norms. Ridge regression (L2 penalty) penalizes the squared L2 norm of coefficients: \(\text{Penalty}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \|\boldsymbol{\beta}\|_2^2 = \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j^2\). Lasso regression (L1 penalty) penalizes the L1 norm of coefficients: \(\text{Penalty}(\boldsymbol{\beta}) = \|\boldsymbol{\beta}\|_1 = \sum_{j=1}^{p} |\beta_j|\). Both penalties measure the “size” of the coefficient vector, but in different ways, and this difference in geometry leads to very different behavior.

Putting it all together, we can generalize OLS by combining any or all of these extensions: \[\hat{\theta} = \arg\min_{\theta} \left\{ \underbrace{\sum_{i=1}^{n} \mathcal{L}(y_i, f_\theta(\mathbf{x}_i))}_{\text{loss function}} + \underbrace{\lambda \cdot \text{Penalty}(\theta)}_{\text{regularization}} \right\}\]

| Component | OLS Choice | Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Function \(f_\theta\) | Linear: \(\mathbf{x}^\top \boldsymbol{\beta}\) | Polynomial, tree, neural network |

| Loss \(\mathcal{L}\) | Squared error | Absolute error, Huber, quantile |

| Penalty | None (\(\lambda = 0\)) | Ridge (L2), Lasso (L1), Elastic Net |

This is the regression toolkit. Different combinations suit different problems. This chapter focuses on linear \(f\) with regularization; non-linear \(f\) comes in later weeks.

5 In-Sample vs Out-of-Sample

When we fit a model, we want to know: How well will it predict new data? Training error (in-sample) measures how well the model fits the data used to estimate it. Test error (out-of-sample) measures how well the model predicts data it hasn’t seen. A model’s training error is almost always an optimistic estimate of its true predictive ability—the model has been specifically tuned to the training data, so of course it does well there!

Overfitting occurs when a model learns the noise in the training data rather than the underlying pattern. To illustrate, we’ll use polynomial regression. Instead of fitting a line \(f(x) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x\), we fit a polynomial of degree \(d\): \[f(x) = \beta_0 + \beta_1 x + \beta_2 x^2 + \cdots + \beta_d x^d\]

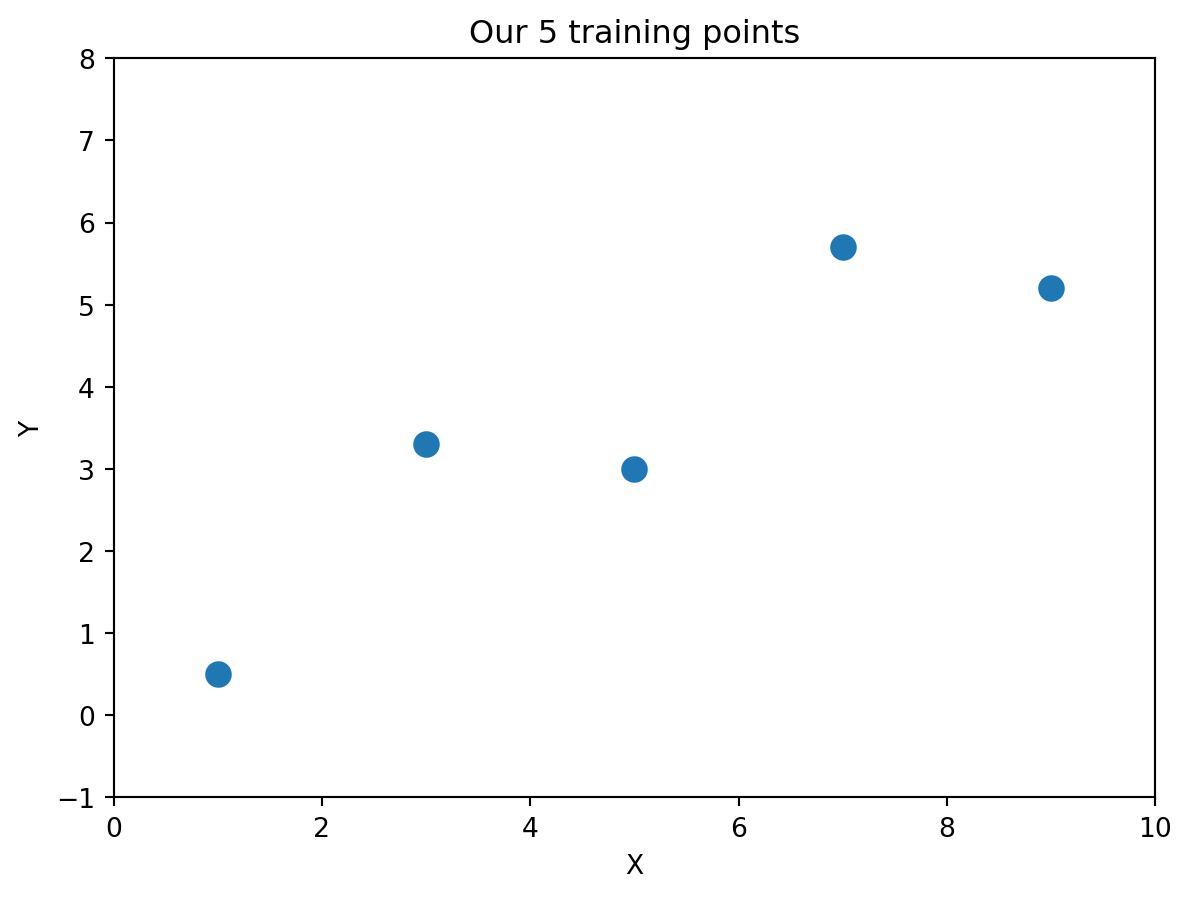

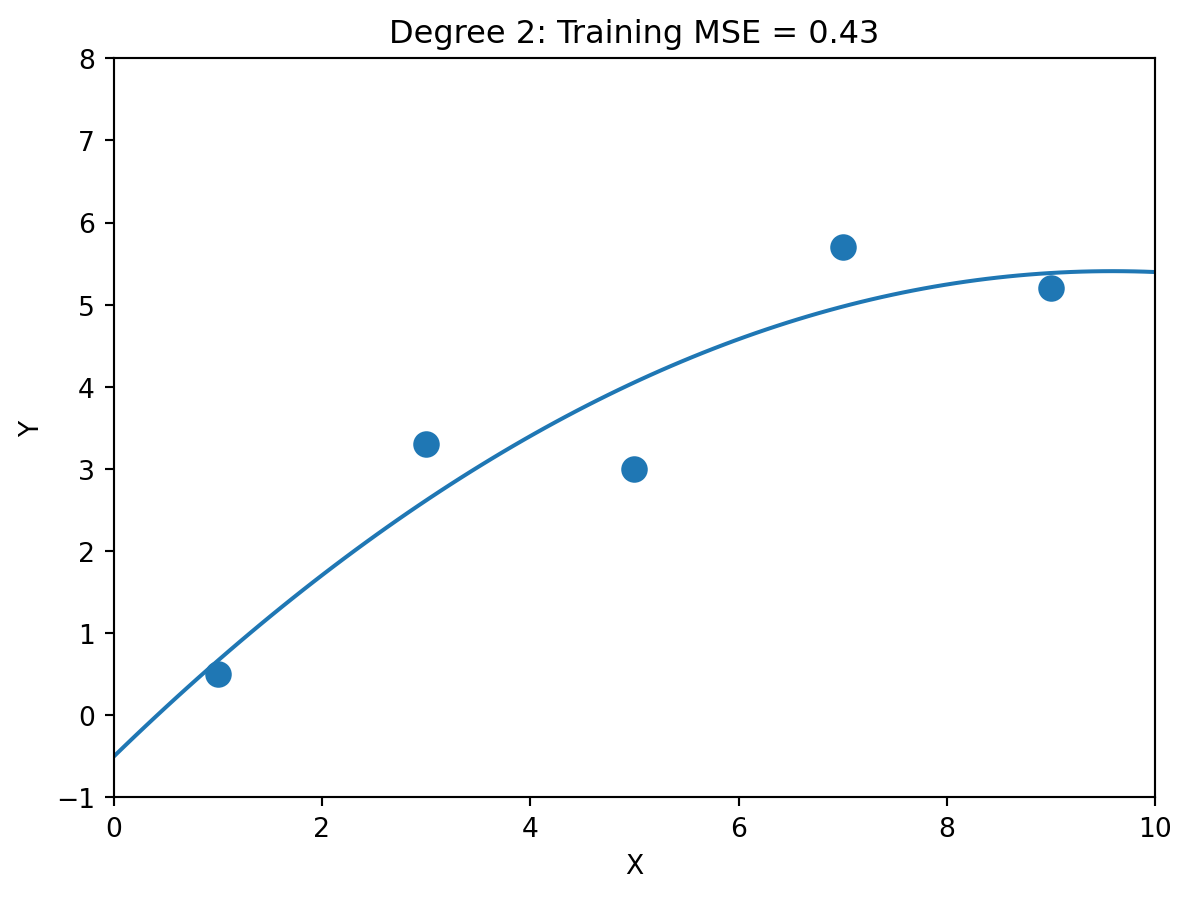

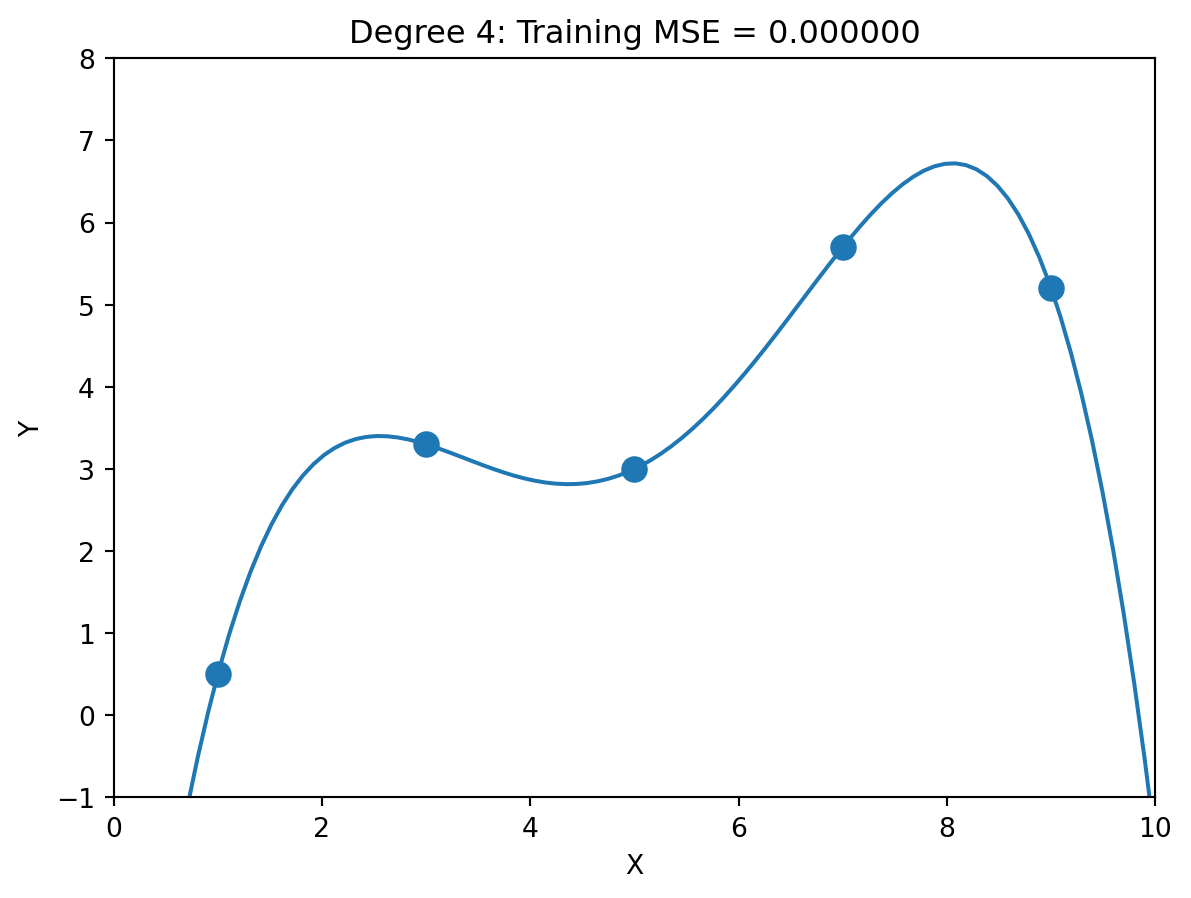

Higher degree = more flexible curve = more parameters to estimate. Suppose we have just 5 data points and the true relationship is linear (with noise):

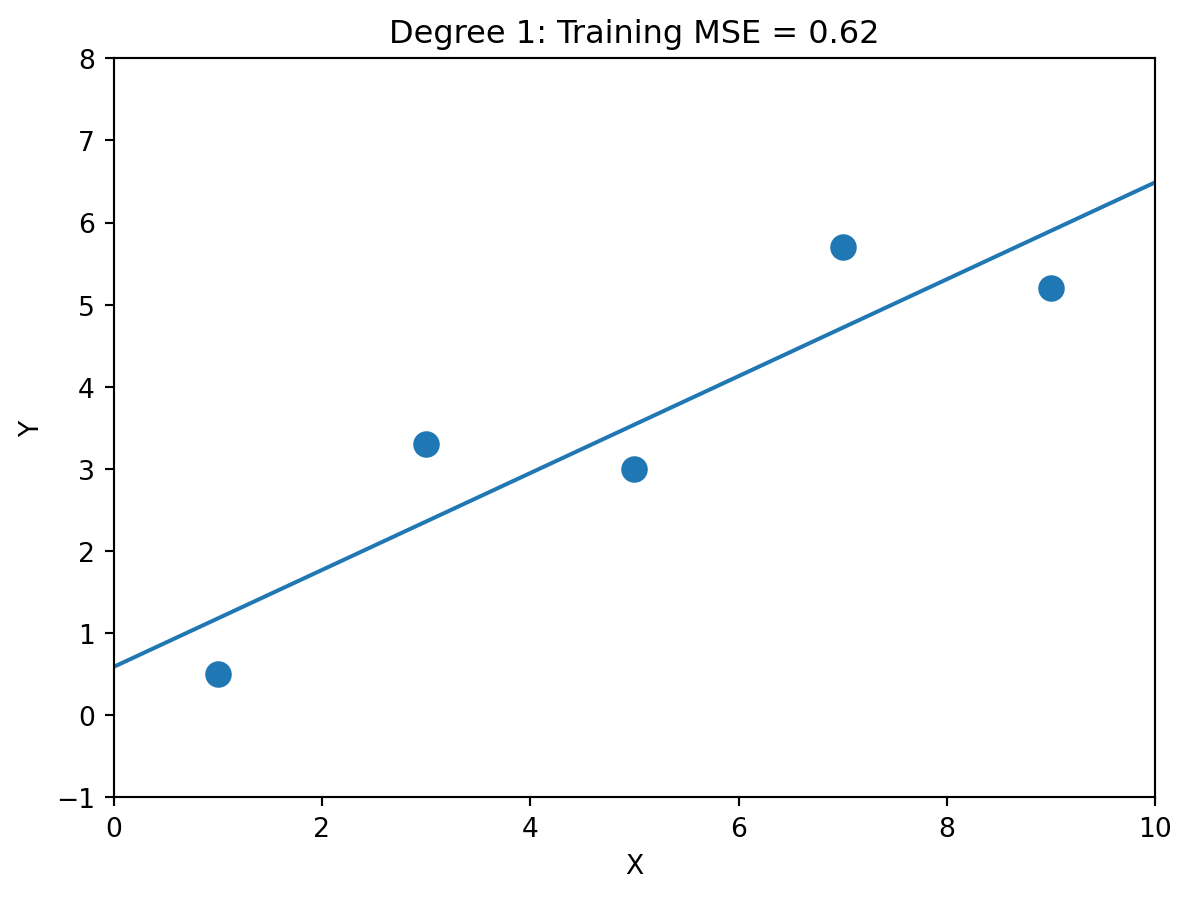

Degree 1 (2 parameters): \(\hat{f}(x) = \hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\beta}_1 x\)

Degree 2 (3 parameters): \(\hat{f}(x) = \hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\beta}_1 x + \hat{\beta}_2 x^2\)

Degree 4 (5 parameters): \(\hat{f}(x) = \hat{\beta}_0 + \hat{\beta}_1 x + \cdots + \hat{\beta}_4 x^4\)

5 parameters for 5 points → perfect fit (MSE ≈ 0). But the wiggles are fitting noise, not signal. And consider extrapolation: if we predict just slightly beyond \(X = 9\) (our last training point), this polynomial plummets—even though the data clearly suggests \(Y\) increases with \(X\). Overfit models can give wildly wrong predictions for interpolating or extrapolating.

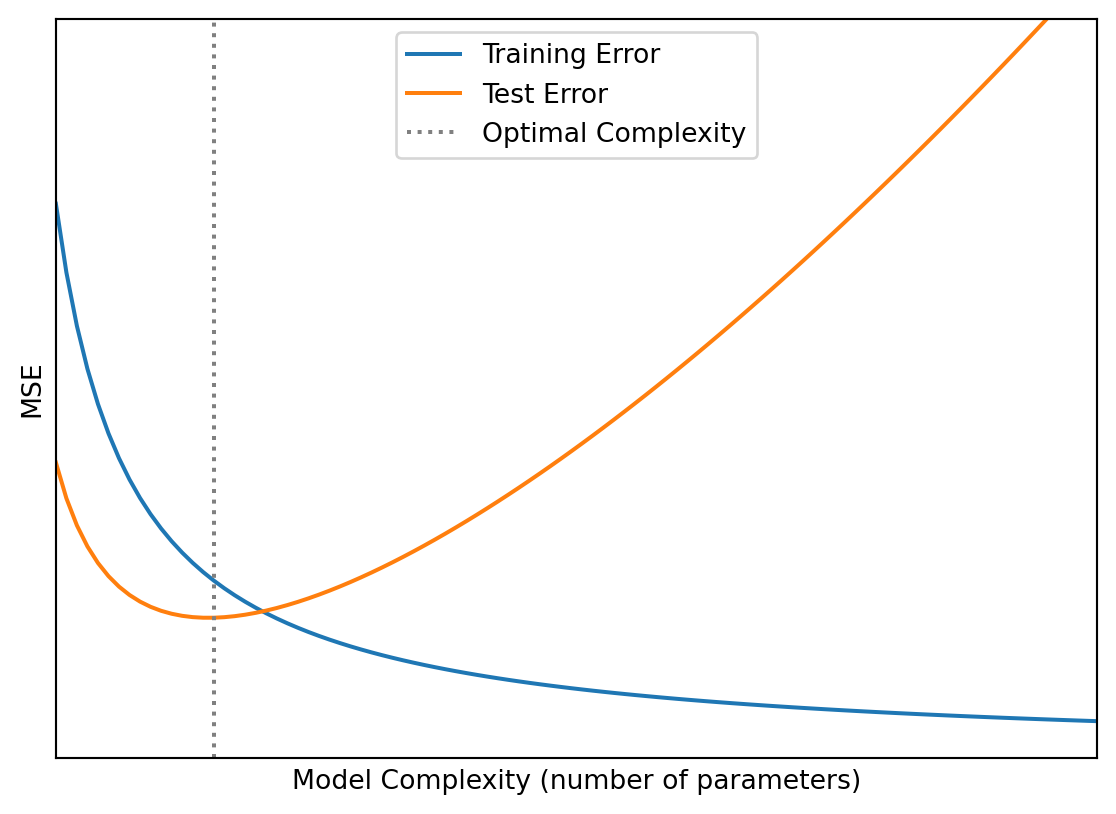

With enough parameters, we can fit the training data perfectly, but perfect fit ≠ good predictions. The model with zero training error has learned the noise specific to these 5 points; on new data, those wiggles will hurt, not help. As model complexity increases, training error always decreases (more flexibility to fit the data), while test error first decreases, then increases (eventually we fit noise). This is the fundamental tension: more complexity reduces training error but may increase test error.

The standard approach to evaluate predictive models is to split your data into training and test sets, fit the model using only the training data, and evaluate using only the test data. The test data acts as a “held-out” check on how well the model generalizes.

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.linear_model import LinearRegression

import numpy as np

# Generate data

np.random.seed(42)

X = np.random.randn(100, 5) # 100 observations, 5 features

y = X[:, 0] + 0.5 * X[:, 1] + np.random.randn(100) * 0.5

# Split: 80% train, 20% test

X_train, X_test, y_train, y_test = train_test_split(X, y, test_size=0.2, random_state=42)

# Fit on training data only

model = LinearRegression()

model.fit(X_train, y_train)

# Evaluate on test data

train_mse = np.mean((y_train - model.predict(X_train))**2)

test_mse = np.mean((y_test - model.predict(X_test))**2)

print(f"Training MSE: {train_mse:.4f}")

print(f"Test MSE: {test_mse:.4f}")Training MSE: 0.1967

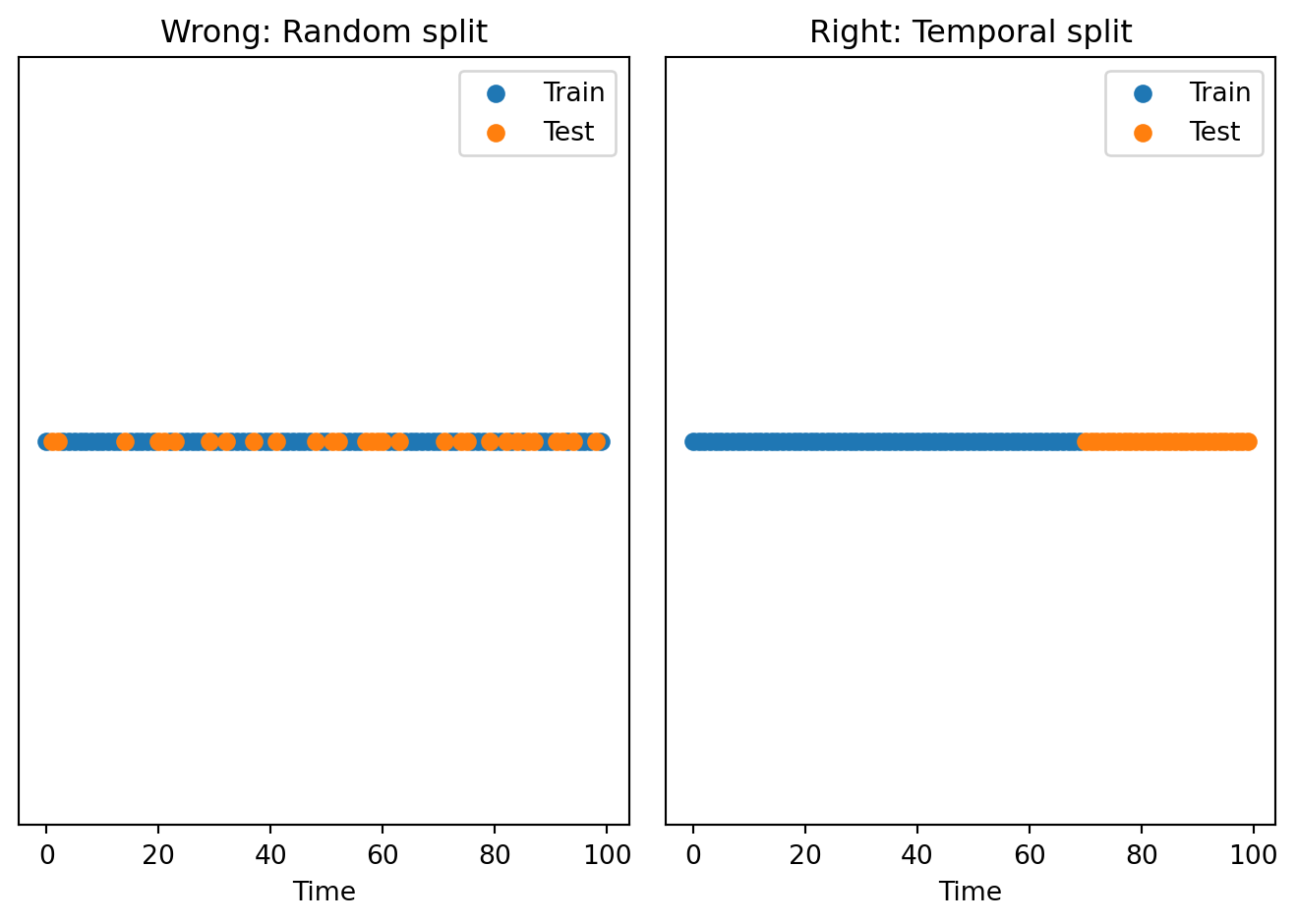

Test MSE: 0.2522In finance, data often has a time dimension, and we cannot randomly shuffle observations. A random train-test split allows future information to leak into training, which is wrong. The right approach is to use a temporal split: train on past data, test on future data.

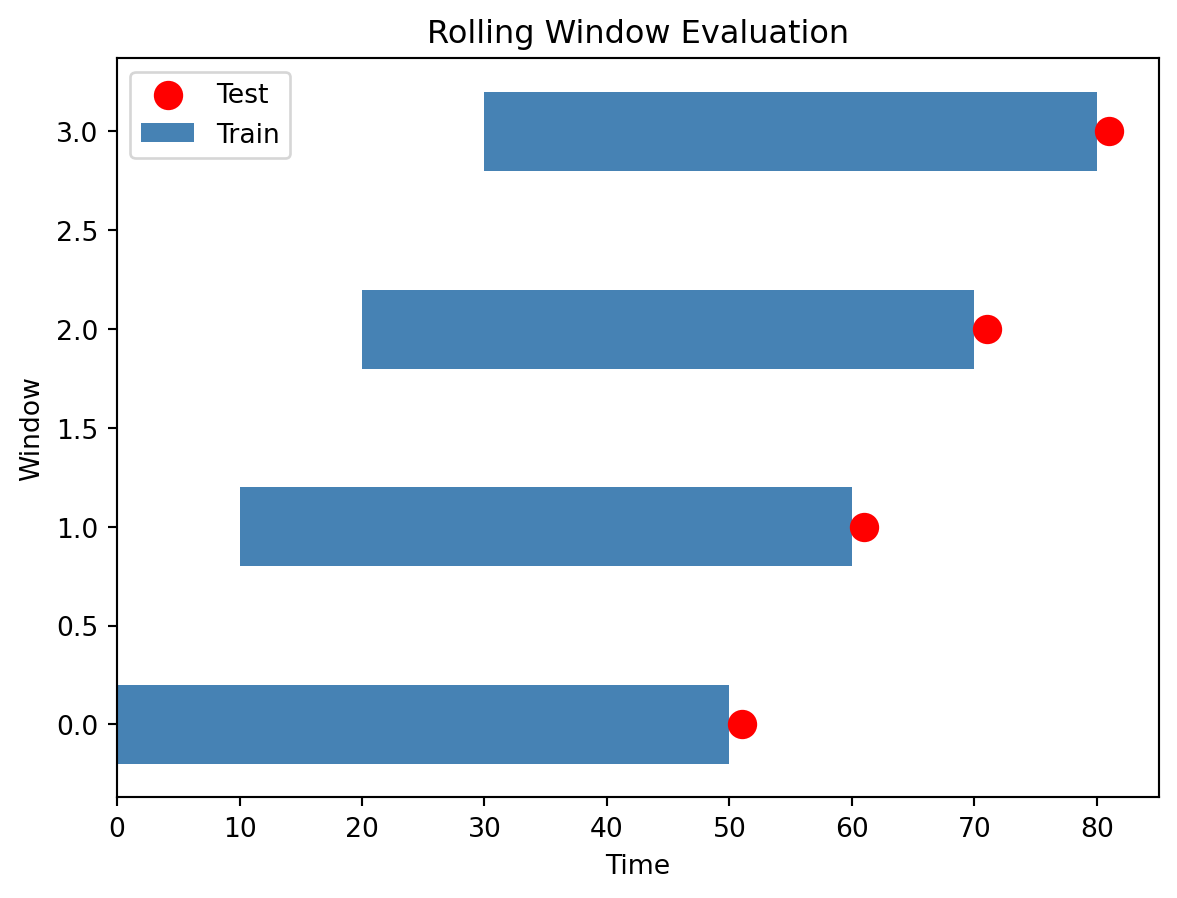

For time series, a common approach is rolling window evaluation: train on data from time 1 to \(T\), predict time \(T+1\); move the window to train on time 2 to \(T+1\), predict time \(T+2\); and repeat. This simulates what an investor would experience: making predictions using only past data.

6 The Bias-Variance Trade-off

When a model makes prediction errors, there are two distinct sources. Bias is error from overly simplistic assumptions—a model with high bias “misses” the true pattern and systematically under- or over-predicts. Think of fitting a constant when the true relationship is linear. Variance is error from sensitivity to training data—a model with high variance is “unstable,” and small changes in training data lead to very different predictions. Think of a high-degree polynomial that wiggles through every training point.

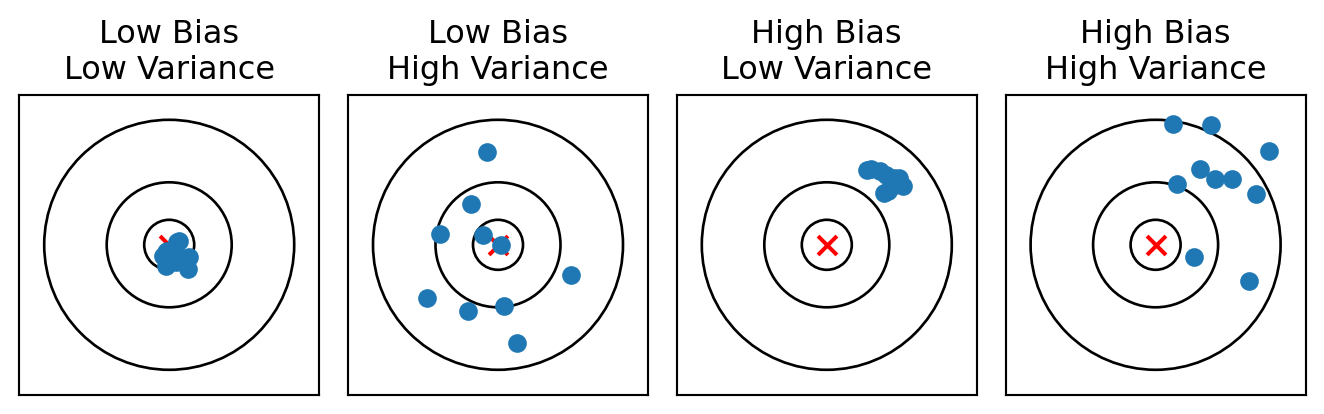

The dartboard analogy helps visualize this. Imagine throwing darts at a target, where the bullseye is the true value:

Low bias with low variance means predictions cluster tightly around the truth (ideal). High variance means predictions are scattered (unstable). High bias means predictions systematically miss the target.

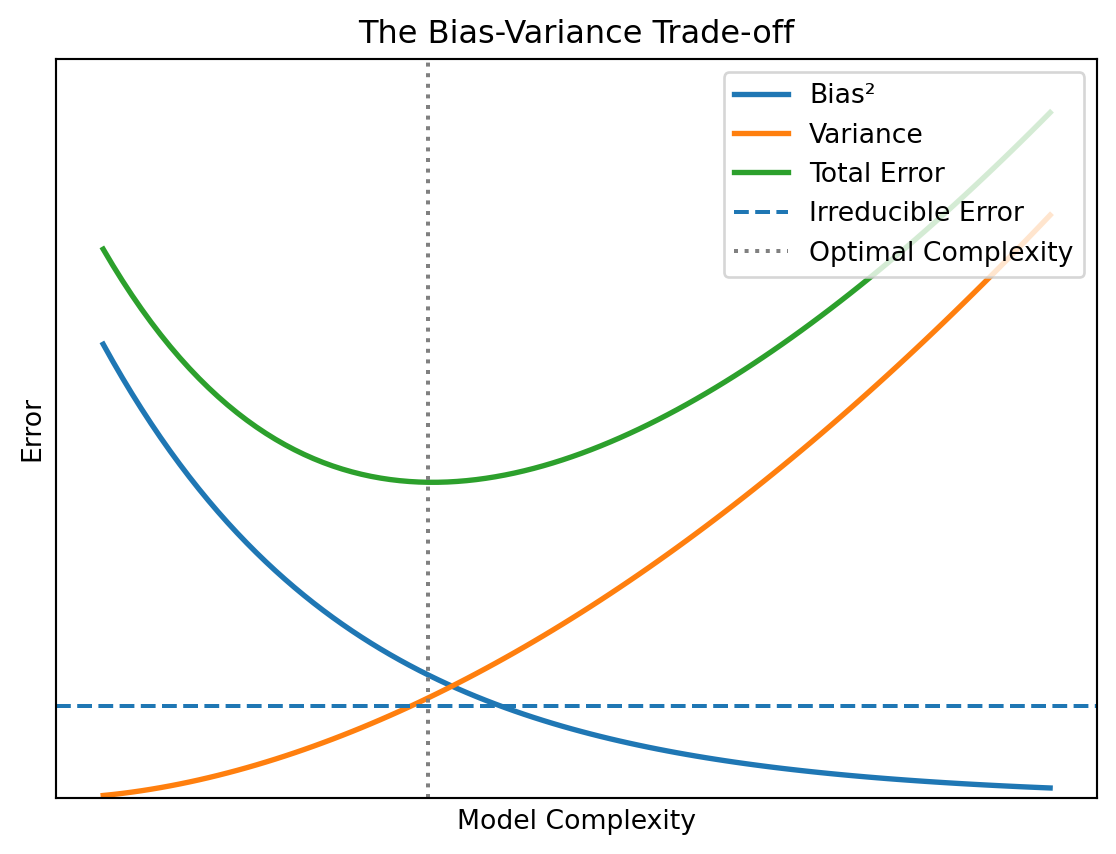

For a given test point, we can decompose the expected prediction error: \[\mathbb{E}\left[(y - \hat{y})^2\right] = \text{Bias}^2 + \text{Variance} + \sigma^2\]

where Bias² measures how far off the average prediction is from the truth, Variance measures how much predictions vary across different training sets, and σ² is the irreducible noise in the data. Total error is the sum of these three terms. We can’t reduce \(\sigma^2\)—that’s the inherent randomness in the outcome.

Reducing bias typically increases variance, and vice versa. Simple models (few parameters) have high bias (may miss patterns) but low variance (stable across training sets)—for example, predicting returns with just the market factor. Complex models (many parameters) have low bias (can capture intricate patterns) but high variance (sensitive to training data quirks)—for example, regression with 50 firm characteristics. The optimal model balances these two sources of error.

As complexity increases: bias falls, variance rises. Total error is U-shaped.

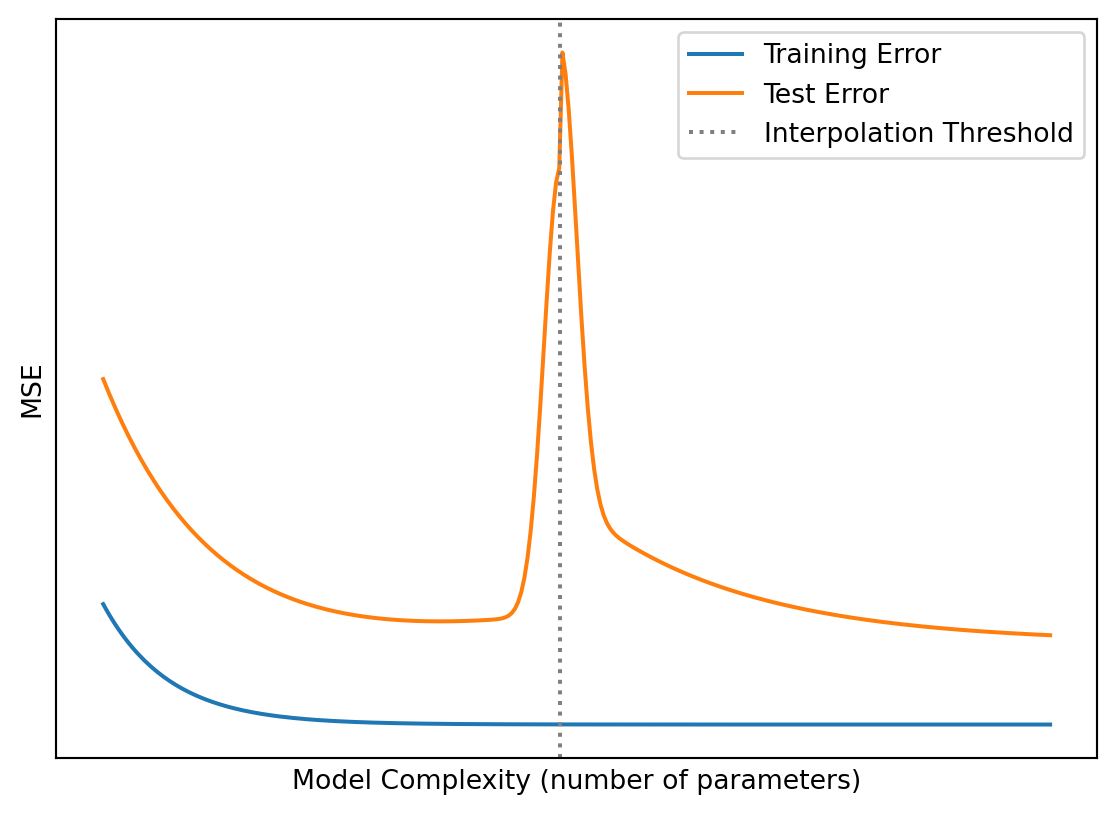

The classical picture says test error is U-shaped. But recent research discovered something surprising: if you keep increasing complexity past the interpolation threshold (where training error hits zero), test error can start decreasing again. This is double descent (Belkin et al., 2019), and it’s been observed in deep neural networks and other highly overparameterized models.

For this course, the classical U-shaped picture is the right mental model. But be aware that the story is more nuanced for very large models—an active area of research. For an accessible explanation, see this excellent YouTube video: What the Books Get Wrong about AI [Double Descent]

Underfitting (too simple) means high bias and low variance—the model doesn’t capture the true relationship, and both training error and test error are high. Overfitting (too complex) means low bias and high variance—the model fits noise in training data, so training error is low but test error is high. Just right means balanced bias and variance, with both training and test error reasonably low.

Where does OLS sit in this trade-off? OLS is unbiased—in expectation, \(\mathbb{E}[\hat{\beta}] = \beta\) (under the standard assumptions). But being unbiased doesn’t mean OLS minimizes prediction error. When the true signal is weak, you have many predictors, or predictors are correlated, OLS estimates have high variance. The variance component of prediction error dominates. Regularization deliberately introduces bias to reduce variance, and for prediction, this trade-off often improves total error.

7 Regularization Methods

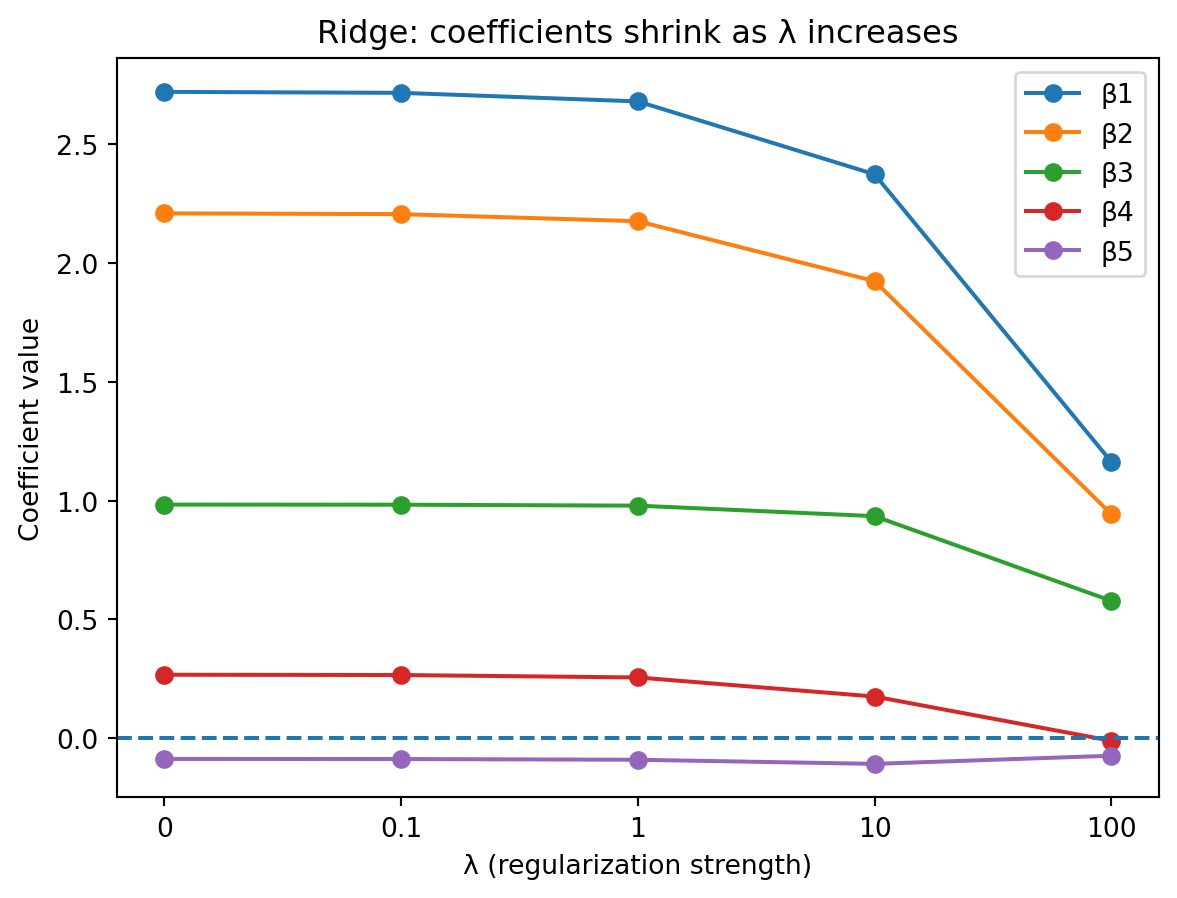

Ridge regression adds a penalty on the sum of squared coefficients: \[\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}^{\text{ridge}} = \arg\min_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \left\{ \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \mathbf{x}_i^\top \boldsymbol{\beta})^2 + \lambda \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j^2 \right\}\]

In matrix form: \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}^{\text{ridge}} = \arg\min_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \left\{ \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}\|^2 + \lambda \|\boldsymbol{\beta}\|_2^2 \right\}\). This has a closed-form solution: \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}^{\text{ridge}} = (\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X} + \lambda \mathbf{I})^{-1} \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{y}\). The term \(\lambda \mathbf{I}\) adds \(\lambda\) to the diagonal of \(\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X}\), making it invertible even when OLS would fail. Ridge regression shrinks all coefficients toward zero, but never sets them exactly to zero. It handles multicollinearity by stabilizing the matrix inversion and reduces variance at the cost of introducing bias.

As \(\lambda\) increases, coefficients shrink toward zero but never reach exactly zero.

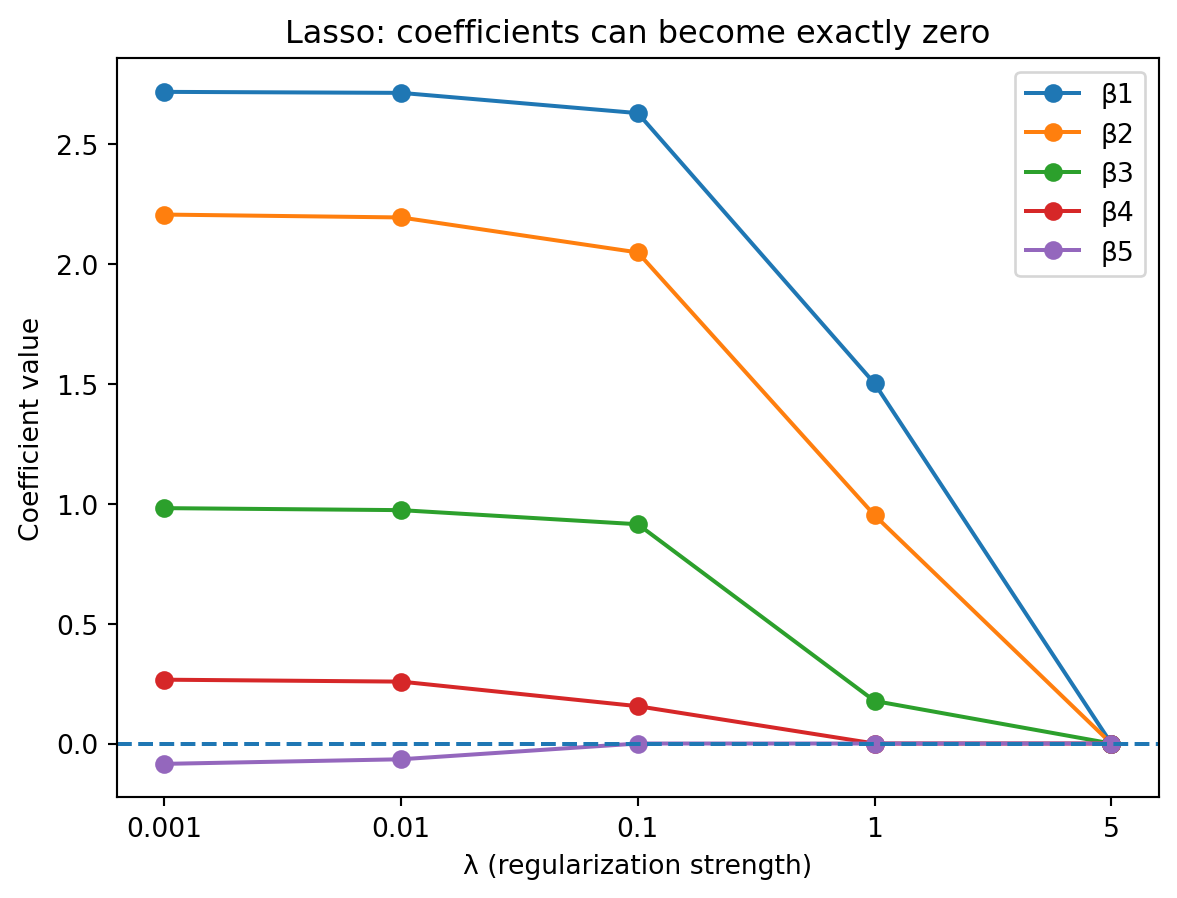

Lasso (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) penalizes the sum of absolute coefficients: \[\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}^{\text{lasso}} = \arg\min_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \left\{ \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - \mathbf{x}_i^\top \boldsymbol{\beta})^2 + \lambda \sum_{j=1}^{p} |\beta_j| \right\}\]

Unlike ridge, lasso can set coefficients exactly to zero. This means lasso performs variable selection—it automatically identifies which predictors matter and which don’t. There’s no closed-form solution; lasso requires iterative optimization algorithms.

As \(\lambda\) increases, some coefficients hit exactly zero—those predictors are dropped from the model.

Use Ridge when you believe most predictors have some effect, predictors are correlated (multicollinearity), or you want stable coefficient estimates. Use Lasso when you believe only a few predictors matter (sparse model), you want automatic variable selection, or interpretability is a priority. In practice, try both and let cross-validation decide.

Elastic Net combines L1 and L2 penalties: \[\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}^{\text{EN}} = \arg\min_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \left\{ \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}\|^2 + \lambda \left[ \alpha \|\boldsymbol{\beta}\|_1 + (1-\alpha) \|\boldsymbol{\beta}\|_2^2 \right] \right\}\]

The parameter \(\alpha\) controls the mix: \(\alpha = 1\) is pure Lasso, \(\alpha = 0\) is pure Ridge, and \(0 < \alpha < 1\) is a combination. Elastic Net is useful when you want variable selection (like Lasso) but predictors are correlated (where Lasso can be unstable).

from sklearn.linear_model import Ridge, Lasso, ElasticNet

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

# Generate data with sparse true coefficients

np.random.seed(42)

n, p = 100, 10

X = np.random.randn(n, p)

true_beta = np.array([2, 1, 0.5, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0])

y = X @ true_beta + np.random.randn(n) * 0.5

# Standardize features (required for regularization)

scaler = StandardScaler()

X_scaled = scaler.fit_transform(X)

# Fit models

ols = LinearRegression().fit(X_scaled, y)

ridge = Ridge(alpha=1.0).fit(X_scaled, y)

lasso = Lasso(alpha=0.1).fit(X_scaled, y)

enet = ElasticNet(alpha=0.1, l1_ratio=0.5).fit(X_scaled, y)

print("True coefficients: [2, 1, 0.5, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]")

print(f"OLS: {np.round(ols.coef_, 2)}")

print(f"Ridge: {np.round(ridge.coef_, 2)}")

print(f"Lasso: {np.round(lasso.coef_, 2)}")

print(f"ElNet: {np.round(enet.coef_, 2)}")True coefficients: [2, 1, 0.5, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0]

OLS: [ 1.74 1.01 0.5 0.01 -0.07 0.03 -0.09 -0. 0.02 -0.03]

Ridge: [ 1.72 1. 0.5 0.01 -0.07 0.03 -0.09 -0. 0.02 -0.04]

Lasso: [ 1.65 0.92 0.4 -0. -0. 0. -0.01 -0. -0. -0. ]

ElNet: [ 1.61 0.91 0.43 0. -0. 0. -0.06 0. 0. -0.01]Before applying regularization, always standardize your features. The penalty treats all coefficients equally, so if features are on different scales, the penalty affects them unequally. For example, if \(X_1\) is market cap (values in billions) and \(X_2\) is book-to-market ratio (values around 0.5), the coefficient on \(X_1\) will naturally be tiny and barely gets penalized while \(X_2\) gets penalized heavily. Standardization (subtract the mean and divide by the standard deviation for each feature: \(z_j = \frac{x_j - \bar{x}_j}{s_j}\)) ensures all features have mean 0 and standard deviation 1, so the penalty affects them equally.

8 Model Selection and Cross-Validation

We need to choose which predictors to include (or let Lasso decide), how much regularization (\(\lambda\)), and which type of model (Ridge, Lasso, Elastic Net, etc.). The goal is to find the model that generalizes best to new data. We can’t use training error—it always favors more complex models. We can’t use all our data for testing—we need data to train the model. The solution is cross-validation.

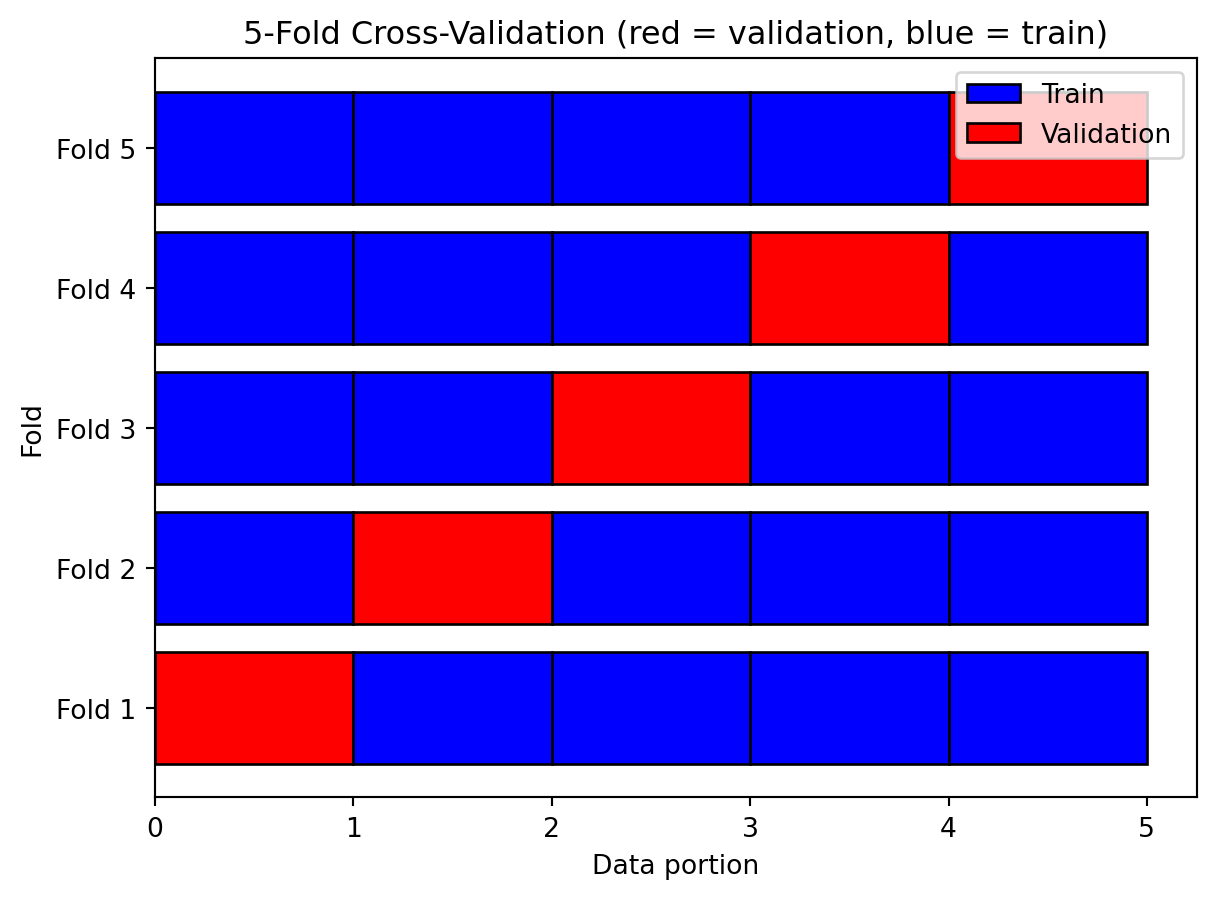

K-fold cross-validation estimates test error without wasting data. Split the data into \(K\) equal-sized “folds.” For each fold \(k = 1, \ldots, K\), use fold \(k\) as the validation set, use all other folds as the training set, fit the model and compute validation error. Then average the \(K\) validation errors. This gives a more robust estimate of test error than a single train-test split because every observation gets used for testing exactly once. Common choices are \(K = 5\) or \(K = 10\).

Each data point is used for validation exactly once. We get 5 estimates of test error and average them.

from sklearn.model_selection import cross_val_score

from sklearn.linear_model import Lasso

# Generate data

np.random.seed(42)

X = np.random.randn(200, 10)

y = 2*X[:, 0] + X[:, 1] + 0.5*X[:, 2] + np.random.randn(200)*0.5

# Try different lambda values

lambdas = [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0]

cv_scores = []

for lam in lambdas:

model = Lasso(alpha=lam)

# 5-fold CV, negative MSE (sklearn uses negative for "higher is better" convention)

scores = cross_val_score(model, X, y, cv=5, scoring='neg_mean_squared_error')

cv_scores.append(-scores.mean())

print("Lambda\tCV MSE")

for lam, score in zip(lambdas, cv_scores):

print(f"{lam}\t{score:.4f}")

print(f"\nBest lambda: {lambdas[np.argmin(cv_scores)]}")Lambda CV MSE

0.001 0.2581

0.01 0.2550

0.1 0.2725

0.5 0.9950

1.0 2.6882

Best lambda: 0.01sklearn provides LassoCV and RidgeCV that automatically find the best \(\lambda\):

from sklearn.linear_model import LassoCV

# LassoCV automatically searches over lambda values

lasso_cv = LassoCV(cv=5, random_state=42)

lasso_cv.fit(X, y)

print(f"Best lambda: {lasso_cv.alpha_:.4f}")

print(f"Non-zero coefficients: {np.sum(lasso_cv.coef_ != 0)} out of 10")

print(f"Coefficients: {np.round(lasso_cv.coef_, 3)}")Best lambda: 0.0231

Non-zero coefficients: 8 out of 10

Coefficients: [ 1.988 1.028 0.43 0.025 0. -0.016 -0.019 -0.017 -0. 0.029]For time series, standard K-fold CV is inappropriate—it randomly mixes past and future. Use TimeSeriesSplit which always trains on past, validates on future:

from sklearn.model_selection import TimeSeriesSplit

# TimeSeriesSplit with 5 folds

X_ts = np.arange(20).reshape(-1, 1)

tscv = TimeSeriesSplit(n_splits=5)

print("TimeSeriesSplit folds:")

for i, (train_idx, test_idx) in enumerate(tscv.split(X_ts)):

print(f"Fold {i+1}: Train {train_idx[0]}-{train_idx[-1]}, Test {test_idx[0]}-{test_idx[-1]}")TimeSeriesSplit folds:

Fold 1: Train 0-4, Test 5-7

Fold 2: Train 0-7, Test 8-10

Fold 3: Train 0-10, Test 11-13

Fold 4: Train 0-13, Test 14-16

Fold 5: Train 0-16, Test 17-19The training set expands with each fold, respecting the temporal order.

9 Finance Applications

In finance, we evaluate predictive regressions using out-of-sample R²: \[R^2_{OOS} = 1 - \frac{\sum_{t=1}^{T} (r_t - \hat{r}_t)^2}{\sum_{t=1}^{T} (r_t - \bar{r})^2}\]

where \(r_t\) is the actual return at time \(t\), \(\hat{r}_t\) is the predicted return (using only information before time \(t\)), and \(\bar{r}\) is the historical mean return (the “naive” forecast). When \(R^2_{OOS} > 0\), the model beats predicting the historical mean. When \(R^2_{OOS} = 0\), the model performs same as historical mean. When \(R^2_{OOS} < 0\), the model is worse than just predicting the mean.

def oos_r_squared(y_actual, y_predicted, y_mean_benchmark):

"""

Compute out-of-sample R-squared.

y_actual: actual returns

y_predicted: model predictions

y_mean_benchmark: historical mean predictions

"""

ss_model = np.sum((y_actual - y_predicted)**2)

ss_benchmark = np.sum((y_actual - y_mean_benchmark)**2)

return 1 - ss_model / ss_benchmark

# Example: model that adds noise to actual returns

np.random.seed(42)

y_actual = np.random.randn(100) * 0.02 # Simulated monthly returns

y_predicted = y_actual + np.random.randn(100) * 0.03 # Noisy predictions

y_benchmark = np.full(100, y_actual.mean())

r2_oos = oos_r_squared(y_actual, y_predicted, y_benchmark)

print(f"OOS R²: {r2_oos:.4f}")OOS R²: -1.4825Negative OOS R² is common in return prediction—the model is worse than the naive mean.

Several factors make financial returns difficult to predict. The low signal-to-noise ratio means the predictable component of returns is tiny compared to the unpredictable component; monthly stock return volatility is ~5%, and any predictable component is a fraction of that. Non-stationarity means relationships change over time—a predictor that worked in the 1980s may not work today. Competition means markets are full of smart participants, and easy predictability gets arbitraged away. Estimation error means even if a relationship exists, estimating it precisely requires more data than we have. Campbell and Thompson (2008) show that even an OOS R² of 0.5% has economic value—but achieving even that is hard.

Common pitfalls in financial ML include look-ahead bias (using information that wouldn’t have been available at prediction time, like using December earnings to predict January returns when earnings aren’t reported until March), survivorship bias (only including firms that survived to the present, excluding bankruptcies, delistings, and acquisitions, which typically makes strategies look better than reality), data snooping (trying many predictors and reporting only those that “work”—if you test 100 predictors at 5% significance, expect 5 false positives; Harvey, Liu, and Zhu (2016) argue t-statistics should exceed 3.0, not 2.0), and transaction costs (a predictor may be statistically significant but economically unprofitable).

Regularization is particularly valuable in finance because of many potential predictors (the factor zoo has hundreds of proposed characteristics), weak signals (true predictability is small; OLS overfits noise), multicollinearity (many characteristics are correlated), and panel structure (with stocks × months, \(n\) is large but so is \(p\)). Studies like Gu, Kelly, and Xiu (2020) show that regularized methods (especially Lasso and Elastic Net) outperform OLS for predicting stock returns out-of-sample.

Before trusting any regression result, check data quality (does the data include delisted/bankrupt firms? are variables measured as of the prediction date?), evaluation (is performance measured out-of-sample? is the OOS R² positive? for time series, is the split temporal, not random?), statistical validity (how many predictors were tried? are standard errors appropriate?), and economic significance (is the strategy profitable after costs? is the sample period representative?).

10 Summary

OLS as optimization: \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}^{\text{OLS}} = \arg\min_{\boldsymbol{\beta}} \|\mathbf{y} - \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}\|^2\). It’s unbiased, but can have high variance when signal is weak or predictors are many/correlated.

Generalizing OLS: We can relax the functional form (\(f\) doesn’t have to be linear), the loss function (doesn’t have to be squared error), and add regularization (penalize coefficient size).

In-sample vs out-of-sample: Training error always falls with complexity; test error doesn’t. This is why we evaluate on held-out data.

Bias-variance trade-off: Simple models have high bias/low variance; complex models have low bias/high variance. Total error is minimized at intermediate complexity. (Though double descent shows this isn’t the whole story for very large models.)

Regularization: Ridge (L2) shrinks all coefficients; Lasso (L1) can set coefficients exactly to zero. Elastic Net combines both. Always standardize features first.

Cross-validation estimates out-of-sample performance and helps choose \(\lambda\). For time series, use temporal splits.

In finance: Prediction is hard (low signal-to-noise, non-stationarity, competition). Use OOS R², watch for look-ahead bias, survivorship bias, and data snooping.

11 References

- Belkin, M., Hsu, D., Ma, S., & Mandal, S. (2019). Reconciling modern machine learning practice and the bias-variance trade-off. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(32), 15849-15854.

- Campbell, J. Y., & Thompson, S. B. (2008). Predicting excess stock returns out of sample: Can anything beat the historical average? Review of Financial Studies, 21(4), 1509-1531.

- Goyal, A., & Welch, I. (2008). A comprehensive look at the empirical performance of equity premium prediction. Review of Financial Studies, 21(4), 1455-1508.

- Gu, S., Kelly, B., & Xiu, D. (2020). Empirical asset pricing via machine learning. Review of Financial Studies, 33(5), 2223-2273.

- Harvey, C. R., Liu, Y., & Zhu, H. (2016). …and the cross-section of expected returns. Review of Financial Studies, 29(1), 5-68.

- Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., & Friedman, J. (2009). The Elements of Statistical Learning (2nd ed.). Springer. Chapters 3 and 7.

- Hull, J. (2024). Machine Learning in Business: An Introduction to the World of Data Science (3rd ed.). Chapters 3-4.

- James, G., Witten, D., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2021). An Introduction to Statistical Learning (2nd ed.). Springer. Chapters 5-6.

More chapters coming soon