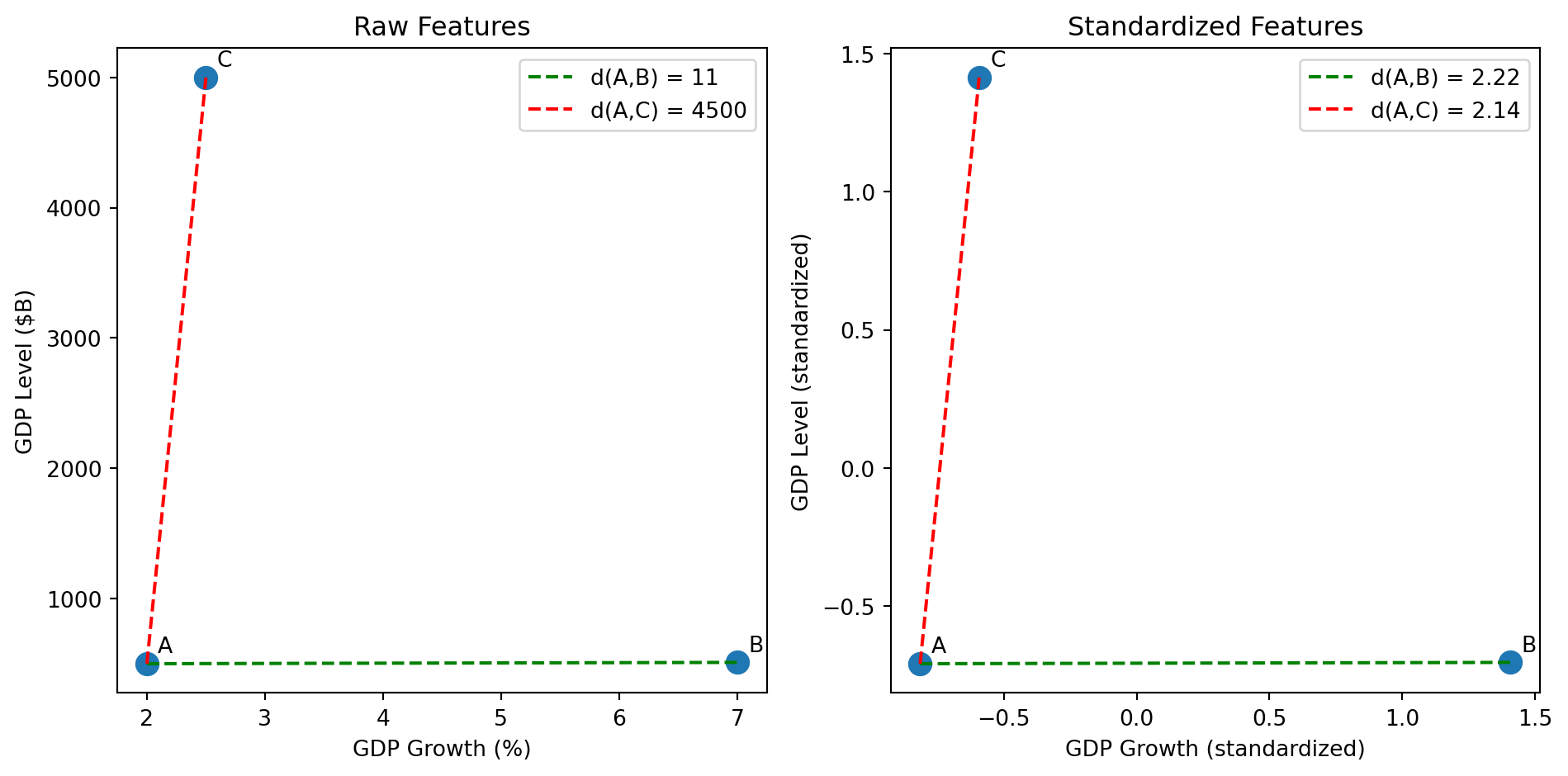

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 2)

# Raw data

X_raw = np.array([[2.0, 500], [7.0, 510], [2.5, 5000]])

labels = ['A', 'B', 'C']

# Compute raw distances

d_AB_raw = np.linalg.norm(X_raw[0] - X_raw[1])

d_AC_raw = np.linalg.norm(X_raw[0] - X_raw[2])

# Compute standardized distances

d_AB_std = np.linalg.norm(X_scaled[0] - X_scaled[1])

d_AC_std = np.linalg.norm(X_scaled[0] - X_scaled[2])

# Left plot: Raw features

axes[0].scatter(X_raw[:, 0], X_raw[:, 1], s=100)

for i, label in enumerate(labels):

axes[0].annotate(label, X_raw[i], xytext=(5, 5), textcoords='offset points')

# Draw lines between pairs

axes[0].plot([X_raw[0, 0], X_raw[1, 0]], [X_raw[0, 1], X_raw[1, 1]], 'g--', label=f'd(A,B) = {d_AB_raw:.0f}')

axes[0].plot([X_raw[0, 0], X_raw[2, 0]], [X_raw[0, 1], X_raw[2, 1]], 'r--', label=f'd(A,C) = {d_AC_raw:.0f}')

axes[0].set_xlabel('GDP Growth (%)')

axes[0].set_ylabel('GDP Level ($B)')

axes[0].set_title('Raw Features')

axes[0].legend()

# Right plot: Standardized features

axes[1].scatter(X_scaled[:, 0], X_scaled[:, 1], s=100)

for i, label in enumerate(labels):

axes[1].annotate(label, X_scaled[i], xytext=(5, 5), textcoords='offset points')

# Draw lines between pairs

axes[1].plot([X_scaled[0, 0], X_scaled[1, 0]], [X_scaled[0, 1], X_scaled[1, 1]], 'g--', label=f'd(A,B) = {d_AB_std:.2f}')

axes[1].plot([X_scaled[0, 0], X_scaled[2, 0]], [X_scaled[0, 1], X_scaled[2, 1]], 'r--', label=f'd(A,C) = {d_AC_std:.2f}')

axes[1].set_xlabel('GDP Growth (standardized)')

axes[1].set_ylabel('GDP Level (standardized)')

axes[1].set_title('Standardized Features')

axes[1].legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()